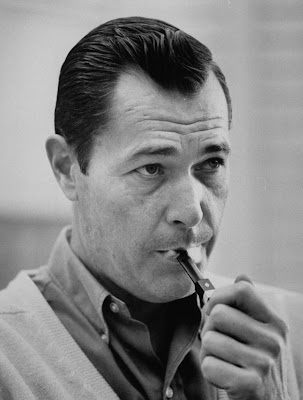

General Ira Clarence Eaker was a general of the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. Eaker, as second-in-command of the prospective Eighth Air Force, was sent to England to form and organize its bomber command. However while he struggled to build up airpower in England, the organization of the Army Air Forces kept evolving and he was named commander of the Eighth Air Force on December 1, 1942.

Although his background was in single-engine fighter aircraft, Eaker became the architect of a strategic bombing force that ultimately numbered forty groups of 60 heavy bombers each, supported by a subordinate fighter command of 1,500 aircraft, most of which was in place by the time he relinquished command at the start of 1944.

Eaker then took overall command of four Allied air forces based in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations, and by the end of World War II had been named deputy commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces. He worked in the aerospace industry following his retirement from the military, and then became a newspaper columnist.

Eaker was born in Field Creek, Texas, in 1896, the son of a tenant farmer. He attended Southeastern State Teachers College in Durant, Oklahoma, and then joined the US Army in 1917.

He was appointed a second lieutenant of Infantry, Officer's Reserve Corps, and assigned to active duty with the 64th Infantry Regiment at Camp Bliss, El Paso, Texas. The 64th Infantry was assigned to the 14th Infantry Brigade on December 20, 1917, to be part of the 7th Infantry Division when it deployed to France.

On November 15, 1917, Eaker received a commission in the Regular Army. He received a Bachelor of Arts degree in journalism from the University of Southern California in 1934.

Eaker remained with the 64th Infantry until March 1918, when he was placed on detached service to receive flying instruction at Austin and Kelly Fields in Texas. Upon graduation the following October, he was rated a pilot and assigned to Rockwell Field, California.

In July 1919, he transferred to the Philippine Islands, where he served with the 2d Aero Squadron at Fort Mills until September 1919; with the 3rd Aero Squadron at Camp Stotsenburg until September 1920, and as executive officer of the Department Air Office, Department and Assistant Department Air Officer, Philippine Department, and in command of the Philippine Air Depot at Manila until September 1921.

Meanwhile, on July 1, 1920, he transferred from the Infantry to the Air Service and returned to the United States in January 1922, for duty at Mitchel Field, N.Y., where he commanded the 5th Aero Squadron and later was post adjutant.

In June 1924, Eaker was named executive assistant in the Office of Air Service at Washington, D.C., and from December 1926, to May 1927, he served as a pilot of one of the planes of the Pan American Flight which made a goodwill trip around South America and, with the others, was awarded the Mackay Trophy. He then became executive officer in the Office of the Assistant Secretary of War at Washington, D.C.

In September 1926, he was named operations and line maintenance officer at Bolling Field, Washington, D.C. While on that duty, he participated as chief pilot on the endurance flight of the Army plane, Question Mark, from 1 to 7 January 1929, establishing a new world flight endurance record. For this achievement the entire crew of five, including Eaker and mission commander Carl Spaatz, were awarded the DFC. In 1930, he made the first transcontinental flight entirely with instruments.

In October 1934, Eaker was ordered to duty at March Field, Calif., where he commanded the 34th Pursuit Squadron and later the 17th Pursuit Squadron. In the summer of 1935, he was detached for duty with the Navy and participated aboard the aircraft carrier USS Lexington, on maneuvers in Hawaii and Guam.

Eaker entered the Air Corps Tactical School at Maxwell Field, Ala., in August 1935, and upon graduation the following June entered the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kan., from which he graduated in June 1937. He then became assistant chief of the Information Division in the Office of the Chief of Air Corps at Washington, D.C., during which he helped plan and publicize the interception of the Italian liner Rex at sea. In November 1940, Eaker was given command of the 20th Pursuit Group at Hamilton Field, California.

Promoted to brigadier general in January 1942, he was assigned to organize the VIII Bomber Command (which became the Eighth Air Force) in England and to understudy the British system of bomber operations; then in December 1942, he assumed command of the Eighth Air Force. A speech he gave the English, and which won him favorable publicity, was,“We won’t do much talking until we’ve done more fighting. After we’ve gone, we hope you’ll be glad we came.”

Eaker drew much of his initial staff, including Captain Frederick W. Castle, Capt. Beirne Lay, Jr., and Lt. Harris Hull, from former civilians rather than career military officers, and the group became known as "Eaker's Amateurs". Eaker's position as commander of the Eighth Air Force led to his becoming the model for General Pat Pritchard in the 1949 movie Twelve O'Clock High.

Throughout the war, Eaker was an advocate for daylight "precision" bombing of military and industrial targets in German-occupied territory and ultimately Germany — of striking at the enemy's ability to wage war while minimizing civilian casualties. The British considered daylight bombing too risky, and wanted the Americans to join them in night raids that would target wider areas, but Eaker persuaded a skeptical Winston Churchill that the American and British approaches complemented each other in a one-page memo that concluded, "If the R.A.F. continues night bombing and we bomb by day, we shall bomb them round the clock and the devil shall get no rest." He personally participated in the first US B-17 Flying Fortress bomber strike against German occupation forces in France, bombing Rouen on August 17, 1942.

Eaker was promoted to lieutenant general in September 1943. However, as American bomber losses mounted from German defensive fighter aircraft attacks on deep penetration missions beyond the range of available fighter cover, Eaker may have lost some of the confidence of USAAF Commanding General Henry Arnold. When General Dwight D. Eisenhower was named Supreme Allied Commander in December, 1943, he proposed to use his existing team of subordinate commanders in key positions, including Lt. Gen. James Doolittle. Doolittle was named Eighth Air Force Commander, and Arnold concurred with the change.

Eaker was re-assigned as Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces, having under his command the Twelfth and Fifteenth Air Forces and the British Desert and Balkan Air Forces. He did not approve of the plan to bomb Monte Cassino in February 1944, considering it a dubious military target, but ultimately "signed off" and gave in to pressure from ground commanders; historians of the era now generally believe Eaker's skepticism was correct and that the ancient abbey at Monte Cassino could have been preserved without jeopardizing the allied advance through Italy.

On April 30, 1945, General Eaker was named deputy commander of the Army Air Forces and chief of the Air Staff. He retired August 31, 1947, and was promoted to lieutenant general in the United States Air Force on the retired list June 29, 1948.

Almost 40 years after his retirement, Congress passed special legislation awarding four-star status to General Eaker, prompted by Senator Barry Goldwater and endorsed by President Ronald Reagan. On 26 April 1985, Chief of Staff General Charles A. Gabriel and Ruth Eaker, the general's wife, pinned on his fourth star.

On 10 October 1978, President Jimmy Carter, authorized by act of Congress, awarded in the name of the congress, a special Congressional Gold Medal to General Eaker, for contributing immeasurably to the development of aviation and to the security of his country.

Eaker died 6 August 1987 at Malcolm Grow Medical Center, Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland, and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.